Ryon Horne/AJC

» Video: Doctors & Sex Abuse: Our investigation so far

Medical regulators pledge that patient protection is their central mission. As part of that focus, their websites provide information to the public about doctors. But in most states, patients will have a difficult time finding out if their doctors have been disciplined for sexual abuse or other violations. And no state provides complete and accurate information on every doctor. Some obstacles to that are intentional. They are the result of state laws that tie regulators’ hands, agreements negotiated with doctors’ attorneys, or concerns about harming a doctor’s practice. Other obstacles reflect a lack of resources or carelessness. Here are some of the gaps, cloaks and barriers The Atlanta Journal-Constitution encountered in its national examination of doctor sexual abuse:

Regulators don’t post key information

Many states issue private letters or orders. Maryland investigated Dr. Joshua R. Mitchell III in 2005 after a complaint that he had sexually violated a patient. During its investigation, the board learned that the Baltimore police sex-crimes unit had investigated a similar complaint from another patient but lost contact with her and didn’t pursue it. The medical board wrapped up its 2005 investigation with a private letter advising Mitchell to offer a chaperone during breast and pelvic exams. Then in January 2010, a patient reported Mitchell raped her during a Christmas Eve exam. The board’s website didn’t provide any information to the public until May 2010, when the board issued an emergency suspension of Mitchell’s license and detailed the complaints. Mitchell is deceased.

Other examples of gaps:

• No mention is made of pending criminal charges. Months after an Indiana doctor was arrested on allegations of raping a patient, the board’s website shows he is licensed, with no discipline. Nothing on the Louisiana medical board website indicates a plastic surgeon is facing criminal charges that include video voyeurism. “Just because a physician has been charged with a crime does not mean that he is guilty,” said Dr. Cecilia Mouton, director of investigations for the Louisiana board.

• Public orders have been taken offline. Kentucky says it often posts only “current” board orders — those still in effect — and others must be requested. Laws in several states require that disciplinary orders be removed after a set period of time. New Hampshire posts only 10 years’ worth of orders.

• No orders are online. Illinois and Wyoming post only summaries of disciplinary actions, which may not detail violations. Arkansas and both of Oklahoma’s boards require the public to file requests for disciplinary orders, and Oklahoma requires a fee. Oklahoma’s osteopathic board, however, said it will have disciplinary orders online by early next year. Mississippi’s website shows if a doctor has been disciplined, but provides no information on the action. A $25 payment is required to see the documents.

In contrast: Maine not only posts orders but provides a phone number for patients to find out if non-disciplinary action has been taken against a doctor. That’s done when evidence supports a complaint but the board decided it wasn’t enough to warrant sanctions.

States don’t detail allegations

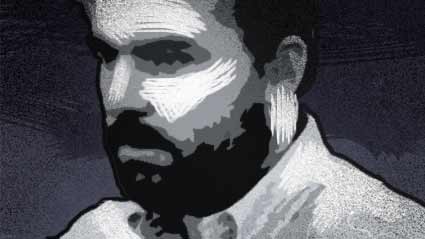

Dr. Manoj Saxena

In Connecticut, a document posted by the Medical Examining Board about Dr. Manoj Saxena says his license is suspended because the board received information regarding “alleged inappropriate contact with a female patient.” That information apparently was his May 2015 arrest on a charge of sexually assaulting an 18-year-old patient. Soon after that arrest, three other female patients came forward with similar allegations. Public court records show Saxena is facing seven felony and misdemeanor counts of sexual assault of four patients in 2014 and 2015, but the medical board can’t disclose that to patients. According to state law cited by board officials, complaints are confidential for up to 18 months, until the board determines their validity. Saxena denies wrongdoing and has pleaded not guilty. He could not be reached for comment.

Other missing information:

More in this series

- System shields doctors’ abuse nationwide, leaves patients in dark

- Why doctors who sexually abuse patients go to therapy, return to practice

- No report, no justice: Doctors sexually abuse patients yet avoid police

- 6 ways abusive doctors may be restricted when they return to practice

- A broken system forgives sexually abusive doctors in every state

- In Georgia, doctor sanctioned 3 times for acts involving vulnerable patients still licensed

- Doctor’s reputation is no indicator of their likelihood to offend

- Medical profession condemns sexual abuse, but resists solutions

• No cause is cited for restrictions. Utah ordered a doctor to continue to use a chaperone when he is treating female patients for “sensitive medical procedures.” But the 2014 order didn’t explain why.

• No reason is given when doctors surrender licenses. Massachusetts allowed a surgeon to resign his license in 2012 without explaining why. However, a reciprocal action for him in Virginia in 2014 says that he agreed not to practice in Massachusetts after he had admitted fondling an unconscious patient in the ICU and other violations.

In contrast: Minnesota orders often detail complaints against doctors.

Disciplinary orders are obscure

Instead of describing a doctor’s offenses, some disciplinary orders refer to legal codes. The 2013 Michigan board order that put Dr. Walter A. Robison on probation said he had been charged with violating “sections 16221(a), (b)(vi), (h) and 16222(3) of the Public Health Code.” Another snippet of information in the order said he “made comments and gestures susceptible of more than one interpretation.” But the board’s administrative complaint, not online but obtained by the AJC, discloses that Robison pleaded no contest in 2011 to misdemeanor assault and battery after a patient complained of his verbal and physical advances on her during an exam. It also says a cancer patient alleged Robison rubbed her breast for no apparent reason and made a practice of straddling her and rubbing his body against hers. Robison could not be reached for comment.

More ways information is cloaked:

• Orders only use vague terms such as “boundary violation” or “unprofessional conduct.” South Carolina in 2008 suspended a cardiologist without disclosing the allegations. In 2013 he agreed to give up his license, and the board cited only “allegations of professional misconduct.” Documents in New York show he had pleaded no contest to aggravated assault and battery for inappropriately touching two patients.

• Passages deleted from orders. Some Kansas board orders can have so much blotted out that they are more white space than print, with red “Confidential” stamps where information would be.

• The severity of the violation is understated. Orders, like one for a Colorado doctor, may refer to sexual relationships with patients and not reveal allegations that sexual activity was forced.

In contrast: North Dakota and Texas orders provide detailed information, and other documents on their websites also provide information on violations.

Websites pose barriers

Dr. Donald E. Nicol

Search Hawaii’s licensing website to check up on Dr. Donald E. Nicol, and a screen appears showing he is in good standing. The page ends with legal disclaimers. Except that it doesn’t end there. Just out of view of the initial screen, if a viewer scrolls down past the legal language, a link to search for complaint histories is nestled. That goes to a lengthy disclaimer that patients must acknowledge to search further. Separated from the first webpage by other links, pages and one more search is a list of dates of pending complaints against Nicol stretching back to 2010, with no explanation. Law enforcement records, however, show he had been charged with 10 counts of sexual assault involving three female patients. He pleaded not guilty. The case was recently dismissed because of a lapsed deadline, though prosecutors could refile. Nicol has called the charges completely false, said his lawyer, Brook Hart.

Other website roadblocks:

• Patients can’t check on doctors without certain specific information. In Vermont, patients would have to know if their physicians are medical doctors (M.D.s or “allopaths”) or doctors of osteopathy (D.O.s or “osteopaths”). Information is in two separate databases that are searched in different ways.

• Links are confusing. The home pages of Montana and Kentucky regulators are full of blind alleys for consumers. Clicking on the wrong link leads to information primarily for doctors.

• Disciplinary actions aren’t clearly labeled. Some states post disciplinary documents under links labeled “board actions,” “public action” or “public record.”

• Multiple steps are required. In New York and Nevada, two searches may be required to get complete information on a doctor because disciplinary orders are in a different place than license information.

In contrast: The Georgia board website has a clear link to look up a doctor, and disciplinary orders are attached to pages about most doctors who have been sanctioned.

Georgia transparency summary:

The Georgia Composite Medical Board posts most disciplinary orders on its website, even for doctors no longer practicing. But in some cases, the website shows that records are only available on request. A more significant transparency issue is the vague information in some orders. For example, a neurologist was sanctioned for being “romantically involved” with a patient for whom he prescribed large quantities of narcotics without proper documentation, and a psychiatrist was put on probation for a “boundary violation” of a female patient. Another gap: Profile information, which is self-reported by doctors, is supposed to list felony convictions, hospital sanctions and other states’ disciplinary actions since 2001. However, the information is not always complete or accurate.

The website itself is relatively easy to use. The home page has a tab for looking up licensee information. The search page asks only for a last name, but that may bring up a long list of doctors. Instead, for better search results, enter the name in the format of last name, first name. The link for viewing public board orders is clearly labeled.

Ryon Horne/AJC